I’d like to address, in my own opinions, the recent announcement of the FDA warning “against the use of devices for diabetes management not authorized for sale in the United States”.

First, there’s a lot of rumors out there and the headlines from the various places trying to “explain” the situation do little to actually give good information. I just did a search to find the link above and let’s just look at those headlines…how many were misleading ledes or otherwise really not getting the whole message correctly explained.

About the only article that really gets it right is the JDRF statement. But, the average person trying to sift through the information this is a very confusing topic admittedly…so let’s pull out some of the specific quotes from the FDA warning and talk about what they mean in plain terms. This really wasn’t about DIY closed loop systems causing harm (although that could be part of it, depending on the situation)…the underlying cause of the warning was about DIY CGM apps.

“The FDA received a report of a serious adverse event in which a patient used an unauthorized device that receives the electronic signal from an FDA authorized glucose sensor and converts it to a glucose value using an unauthorized algorithm. Glucose values from this unauthorized continuous glucose monitoring system were sent to an unauthorized automated insulin dosing device to drive insulin dosing. The automated insulin dosing system gave too much insulin in response to repeated incorrect high glucose values sent from the [unauthorized] continuous glucose monitoring system (emphasis added). This unauthorized system resulted in an insulin overdose requiring medical intervention. ”

Before we can look at what this means…it would be helpful for many people to have a really basic introduction to continuous glucose monitors (and this is the really layman version).

CGM basics

Glucose sensors don’t actually read a blood glucose reading. Instead they read a “raw signal,” basically an electrical signal from the fluid surrounding the sensor wire. That raw signal is then converted to a “blood glucose reading” by an algorithm. The algorithm that does that job is a HUGE chunk of work by the company that makes the sensor. They do lots of design, testing, clinical trials, and reworking on that algorithm. That algorithm is really, really important for demonstrating that the sensor will be safe for the users in a variety of situations. For example compression lows, poorly timed calibrations, and rapid temperature changes are just some of the difficult situations that an algorithm will need to deal with.

Dexcom sensors showing ??? or “sensor error, wait up to 3 hours”…that is actually a part of the safety algorithm. The sensor wire’s raw signals are either varying wildly, perhaps the calibration entered is way out of its expected bounds, or the temperature suddenly shifted a lot. The sensor algorithm is rightly telling you “Hey, I’m unsure about telling you a number and I don’t want you doing something unsafe with a number I’m not sure about. Give me a chance to see if the raw signals settle down again.”

All sensors on the market have safety checks and sensor failure communications built into their algorithms. They also have enforced end-of-sensor (for example, Dexcom G6 is 10 days) timing in the apps. These features are all part of the safety of using CGMs for diabetes management decisions, and they undergo FDA review.

X-Drip and Spike Apps

Have you ever just wanted to avoid the ??? or enforced end-of-sensor sessions? I know you have because this blog’s post on how to restart a Dexcom G6 is one of the most popular blog posts I’ve ever written.

There’s two DIY CGM apps on the market that avoid those ??? and session ends. The apps (X-drip for Android phones and Spike app for iPhones) are popular in part because they offer the ability to just “always get CGM data”. While nice on the surface, those features can present a problem potentially…and that’s what the FDA warning was all about.

X-drip and Spike use their own algorithms to handle the raw signals. Calibrations, temperature variations, sensor noise, sensor failure notifications and other variables within the algorithm are not clinically-tested for those apps. (note: Generally, X-drip and Spike use the same algorithms between the two apps for several of the supported CGM devices. Therefore, X-drip and Spike are generally going to behave the same when we are discussing the general topic of DIY CGM apps.)

Reported Adverse Event

So what happened to trigger the FDA warning?

Plain and simple…a person was using a Libre sensor on one of these DIY CGM apps. Libre sensors are not continuous glucose monitoring devices. They are flash glucose monitors. In order to make them into continuous glucose monitors, some people have used non-FDA approved devices that sit on top of the Libre sensor to emulate someone “flashing” their Libre for a reading. Those devices you probably recognize as either the Miao Miao or Blucon readers.

Since these readers are not officially associated with Libre sensors…there’s also no clinically-tested, FDA-approved app to receive the information from these readers. And this is where the warning comes in:

“The FDA received a report of a serious adverse event in which a patient used an unauthorized device that receives the electronic signal from an FDA authorized glucose sensor and converts it to a glucose value using an unauthorized algorithm….repeated incorrect high glucose values [were] sent from the [unauthorized] continuous glucose monitoring system…”

Someone using (1) a Miao Miao reader and (2) a Libre sensor and (3) a DIY CGM app had a situation where the sensor failed. Instead of the sensor failing by then reporting no data (such as ??? or “sensor error” like Dexcom), the DIY CGM app showed incorrectly high BG readings.

What does this look like?

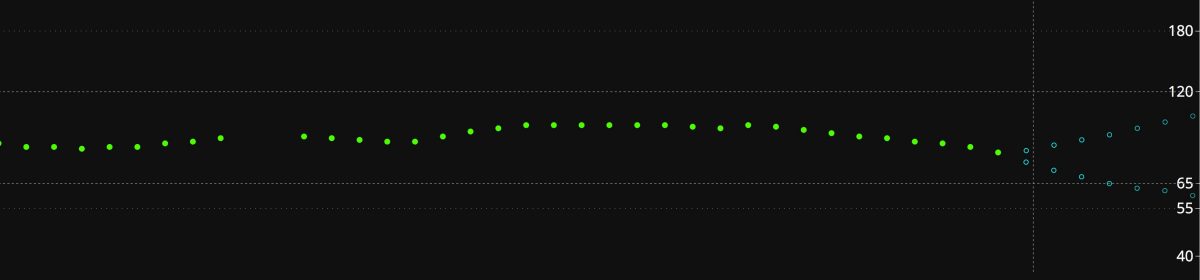

The image above is from another recent report very similar to the one discussed in the FDA warning (minus the need for medical intervention). Details of this event can be found in the OpenAPS Github repository.

The user had Miao Miao + Libre sensor + DIY CGM app. The recently restarted sensor started to fail with a drift. The user, rather than pull the failing sensor, tried to calibrate the sensor to the 16 mmol (about 288 mg/dL) value shown near 10am. The failed sensor took the calibration and remained virtually stuck. The DIY CGM app continued to report nearly 16 mmol for 8 hours…

So, let’s stop there and assess.

- Are we irritated when sensors stop providing data and instead say ??? or “sensor error”? Yes.

- Are sensors expensive and we try to get them to work as long as they can? Yes, many people do.

But, if automated insulin dosing is also a part of someone’s DIY CGM app use…those safety factors (and your ability to do without them) may need to be re-evaluated in terms of whether or not you want to continue to make insulin dosing decisions on them. Can commercial CGM algorithms still get data wrong? Yes, but it is far less common these days…and if they do get data wrong, it is very unlikely to be so “off” that an automated insulin delivery system would cause a hypoglycemic event serious enough to cause medical intervention.

Automated Insulin Delivery

The FDA-reported problem of the failed sensor still sending bad CGM readings through the DIY CGM app…it affected the user’s DIY closed-loop automated insulin delivery and caused the system to over-deliver insulin. The user needed hospitalization for the hypoglycemic event that occurred as a result.

The figure above with the 16 mmol? See below the royal blue marks at the bottom of the figure? Those were automated insulin microboluses delivered by the user’s OpenAPS system to try to bring down the 16 mmol. If unnoticed by the user, those insulin deliveries could have caused hypoglycemia.

Is this potential to over-deliver (or under-deliver) insulin unique to DIY closed-loop systems? Nope, absolutely not. And that is the message that all this news coverage is missing. The REAL story. Access to quality CGM devices is the underlying need to be addressed.

Any automated, closed-loop system (commercial or DIY) will only be as good as the CGM data that is feeding the system.

Medtronic’s 670G system will kick users out of automode when their algorithm has sensor issues. All commercial closed loop systems will have safety checks that if the CGM part of the system reports an error…you’ll be kicked back to old-school insulin dosing decisions.

CGM Data is Critical

Now that we’ve addressed the background, it is pretty obvious just how important keeping quality CGM data is if you choose to use any closed-loop system.

Only one iCGM system, the Dexcom G6, is currently FDA-approved for eventual automated insulin dosing across future integrated pump/loop systems (Medtronic’s 670G’s Guardian 3 sensor is approved only for their system in particular). This is the system we use and I love it. I feel very safe with its use and messaging. The first 8-12 hours are a little jumpy and I can choose to open loop if I want to…but otherwise the sensor has proven to be exceptionally accurate for the 10 days we use it. Despite the fact I wrote the blog post about how to restart, we actually don’t restart our G6 sensors. Anna enjoys fresh clean adhesive and the insertion is so easy for her that it isn’t an impediment to change sensors any more.

Unfortunately, many areas outside the USA do not have access to or approval of Dexcom G6. This leaves them either incredibly expensive or entirely unavailable. The Libre sensors are more widely available and/or affordable in those markets…giving rise to this dilemma about DIY CGM apps.

Ideally, the FDA’s warning message hammers home a point that really is sorely true. The access to quality health tools to safely manage T1D is lacking. T1D is so inherently risky. The slowness of the world’s government systems to help with access and affordability of quality CGMs is adding to our community’s collective risk.

Dear FDA…if access and affordability of quality CGM systems were addressed, DIY CGM apps would not be needed. Adverse events can happen on your FDA-approved devices as well. T1D is risky with syringes and finger sticks through the most advanced FDA-approved closed loops. The warning is that diabetes is risky, and we need quicker iteration and better development in the commercial markets.

People might not necessarily want to use a Libre plus a reader plus a DIY app…but in some cases they’ve assessed their risk management baskets and decided that setup IS their best risk mitigation.

To those people, please…

- be exceedingly careful about not extending sensors to beyond their safe lifespan,

- make very careful calibration decisions,

- watch for signs that the sensor wire as even partially pulled out of skin, and

- if in doubt, change your sensor and take finger stick readings.

For us personally, we are grateful to have an iCGM (Dexcom G6) and that we can afford to change it regularly. We use the official Dexcom app because those times of “sensor error” or “???” provide a level of safety that I find appropriate, rather than an annoyance, since we are using a closed-loop. We replace sensors when they show any sign of failure, and I don’t feel in the least bit guilty about it. And the use of our DIY Loop app has decreased our overall risk exposure while managing T1D…but I can only say that because our CGM data is reliable. And that’s what the FDA warning was trying to tell you.

Very well worded and informative.

Thank you

Hi Katie, I think a few groups, including healthcare systems, might take umbrage with your statement about it being upon them to reduce the cost of access to CGM.

Abbott significantly lowered prices, in line with the cost of SMBG 8 times daily to get the adoption with healthcare systems they have seen in many parts of the world. Dexcom has, thus far, not done the same, leaving their prices very much tilted towards the US insurance system.

I’m not saying it should all be on the manufacturers, but there needs to be a reasonable approach from both sides.

OUTSTANDING!!!!!!!!! Bravo, Katie!!!!!!!!!

Great post although I think it’s worth to mention that xdrip defaults to the native algorithm with the G6 and it’s not easy to turn it off and use the xdrip algo (you need to enable engineering mode otherwise it’ll always fall back to native mode)

Love this. Thank you for explaining so beautifully!

great article, beautifully written which i think perfectly describes the ongoing risk/benefit balance around CGM tech “repurposing”

the key is ensuring that risks are recognised and incorporated into (non-algorithmic) decision-making rather than devices and their use being stigmatised